In Korean folklore, there is a legend of a nine-tailed fox, named Kumiho. Her tale dates back to the Three Kingdoms of Korea era (approximately 57 BCE to 668 CE). Foxes were thought to be goddess-like spirits who could live for thousands of years. Kumiho is a shapeshifter, a half-human half-fox, who travels between the realms of fantasy and reality. She is always adorned with yeowoo guseul – magical beads that feed Kumiho with power and give power to regular people who are able to swallow them. Some versions of her stories depict her tricking kings into falling prey to her charms as she climbs to royalty, hunting and capturing men to harvest their livers and hearts. Other stories tell of her tricking young boys into forests as she disguises herself as a human. In each of these stories, however, Kumiho yearns to be completely human, no longer stuck between “normal” and “other”.

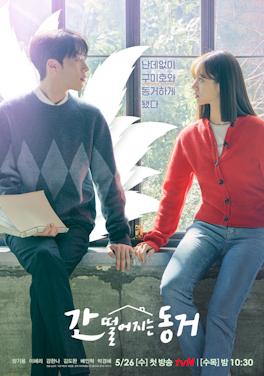

In modern retellings of Kumiho, like the two Korean-Dramas My Roommate is a Gumiho and Tale of the Nine-Tailed, the fox-humans are given more storyline and perspective. The television series portray them as misunderstood fox-spirits who, in their human forms, search for lost loves and fight evil supernatural beings. These redemption arcs for Kumiho are interesting, innovative, and necessary, yet in both retellings, the kumiho are men. How come all it took to see Kumiho in an alternate light was to change her gender? The older legends of Kumiho are based on misogynistic philosophies that women are sneaky, tricky, and untrustworthy, especially towards men. In one tale, an expecting couple wishes for a daughter (something that was unheard of and unexpected, especially during older time periods in Korea). When they finally give birth to a daughter, it is later discovered she is a conniving, evil kumiho and her brother slays her, becoming the hero in the story.

Promotional poster for My Roommate is a Gumiho

Promotional poster for Tale of the Nine Tailed

While much has changed since the origin of Kumiho, patriarchal structure still stands strong, and as evidenced in the K Drama retellings, the fox literally had to change gender to gain sympathy. With my piece, I highlight how women have been treated for centuries, and how women are still treated today. The four women tell the story of Kumiho, but more importantly, tell the story of themselves. I think the anger we portray throughout the piece can be empathized by all women.

Now that I’m older, I see Kumiho all around me. I see her in my family members; my halmoni, who had to shapeshift when she immigrated to the United States, changing her names, shifting her careers, leaving behind her old life to travel to a new one where she was constantly viewed as “other”; my mother, who was told from an early age to be the proper model minority – to get good grades, never speak back, and marry a successful man; and myself, a young woman living between two races, two cultures, a figurative mix of “fox” and “human”.

I am not full Korean. I have only visited South Korea twice, and I barely know the family I have left there. I don’t speak the language (my halmoni immigrated to the US when my mom was three and refused to keep up with teaching her Korean, only speaking to her in English) and my family doesn’t celebrate most cultural traditions. I have lived most of my life walking between two worlds, wondering if things could be easier if I was ever “fully” something.